When scaling agile, it’s important to keep front of mind that we are spending other people’s money. We should always think about delivering value for money from outset and be transparent with ourselves and stakeholders about Value. A sponsor will ask the questions “Are we getting value for money?” and/or “Can’t we go faster?”. These are legitimate challenges and as responsible professionals we need to have explored the options before adding more people and therefore cost.

So before you add people, what can you do to deliver more, faster?

To get to an effective delivery, here are the things I look at. After the first point, they are in no particular order as the priority will differ depending on the circumstances. I’m assuming there’s already a team in place and they’re already delivering.

Culture – Is there an open, supportive, learning culture?

If this isn’t in place, your team is neither as efficient or effective as it can be. Even hints of a closed, niggly culture will mean people are not looking to learn and motivation / productivity will wither.

What’s worse is that scaling even a mediocre culture will exaggerate the flaws exponentially and the negative traits will overwhelm anything positive. Your good people will leave, your initiative will start to fail.

User stories – Are your stories really ready to be played?

Particularly in the early days of delivery, there’s a tendency to underestimate the level of information needed to write the code and tests that deliver a user story. The concept of a user story being the “invitation to a conversation” can also be used as an excuse for not writing down the key aspects of delivering a feature.

The dialogue triggered by writing acceptance criteria, producing designs, estimating, defining performance is critical to both effective and efficient delivery.

So create a “definition of ready”, make sure that all your stories meet it before they are played. Then improve it as part of your regular retrospectives; there’s no such thing as a perfect story.

Prioritisation – Are you really working on the right things in the right order?

This is an interesting one as the simplistic Agile mantra is that you should be always working on the most valuable feature to the organisation at any time. In theory this is focusing on being effective, however this mantra can drive inefficiencies.

From the perspective of a user, there will often be groups of features that only make sense to deliver together or in a specific delivery order. From a technical perspective there are usually a set of foundations that are better to be in place early to limit the amount of refactoring that would have to be done if they are implemented later. In both cases the high value features might be more efficiently delivered later.

As usual, the key here is balance. Use the high value features as a goal or mission and recognise that putting some foundations in place are important to minimise “throw away” work. This requires careful facilitation of business, delivery and technical perspectives.

Frameworks – Have you got the right frameworks in place?

This is a relatively obvious one. In any software delivery many of the concepts will have already been delivered by someone else as reusable components, creating these again is wasteful. Most of the common ones will be already available in e.g. .NET and Java frameworks.

For the new features that you are developing, if you find common patterns build them into the frameworks so that the next time they are needed development is accelerated.

For a one team delivery switching technical framewoks might be managble, however once you have many teams there is a massive switching cost.

As part of your Discovery / Foundations, pick a framework that works for your product, stick to it and extend it as necessary. Avoid mixing or switching frameworks as this generates confusion and context switching.

This goes a little against the concept of emergent architecture but again balance / pragmatism is important.

Environments – Is your build, test and deploy pipeline mature?

Again this might seem like an obvious one but every large programme I’ve seen has problems getting continuous integration and continuous delivery sorted, mainly because it is complex and there are important (but unexciting) operational aspects, such as security, logging, audit, user support, back-up and recovery to get right.

There’s little more frustrating for delivery people than being able to demonstrate code to users that want to use it but can’t. It’s one of those foundations mentioned earlier, you have to get your build and deploy pipeline in place before you can deliver working code. In extremis, stop writing code and send everyone not involved in generating it on holiday until your pipeline works.

“Right-plating” – Do you have an appropriate definition of done for the product / service you are delivering?

In the drive to get software live, particularly for an alpha or pilot, it is very tempting to cut corners in non-functional and operational acceptance testing. Conversely an operations function, typically coming from an ITIL mindset, will typically look to over-document from habit and training.

The phrase “an appropriate level of rigour” is key here.

Your definition of done must include non-functional requirements such as maintainability, performance and security, but have you created a cottage industry of operational acceptance documentation? Can you automate production of the documentation that is really needed?

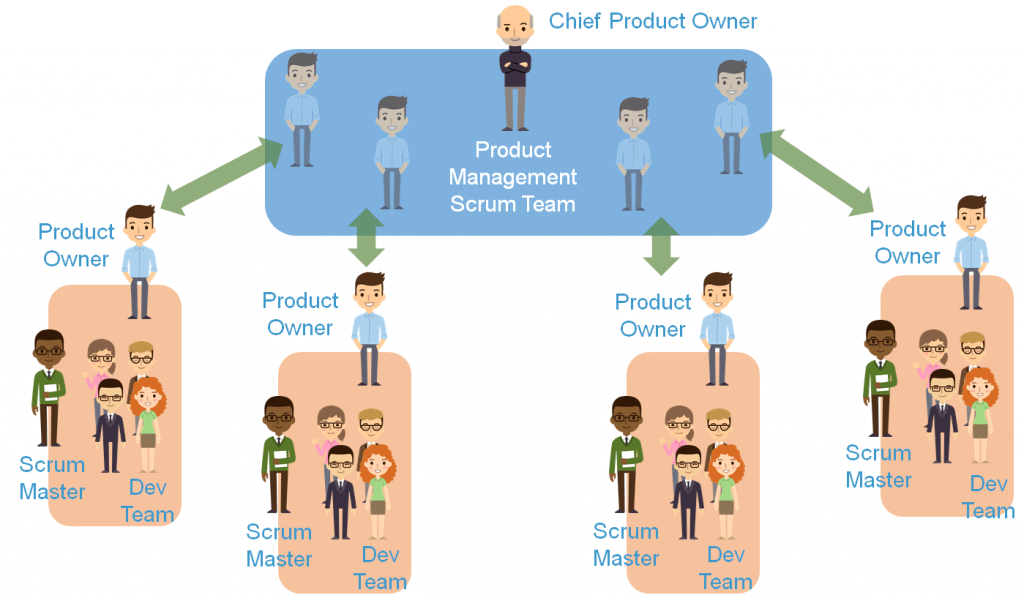

Delivery Organisation / Process – Are you set up the right way for your product / service ?

Adhering evangelically to just one Agile/Lean methodology is a recipe for poor productivity. The core of Agile is the same in all methods but, for anything other than the simplest deliveries, you need lean principles, the software engineering disciplines of XP, the management disciplines of DSDM, the focus on culture in Scrum. The blend will depend on your circumstances but you will need some of all of them. Note you don’t need SAFe at this stage (if at all)

Make sure the team completely focussed on delivery. Minimise the number of people that are not dedicated to the team and make sure that when they are with the team they are not distracted by their other responsibilities. This is particularly true of Product Owners given their key role in delivery. I think that PO’s having some operational contact is good, as they stay up to date with the current user journeys and needs, the issues come when they are still responsible for operations because a business-as-usual problem can completely de-rail delivery.

Develop and maintain a disciplined rhythm

Context switching ruins productivity. Unregulated feedback is just noise.

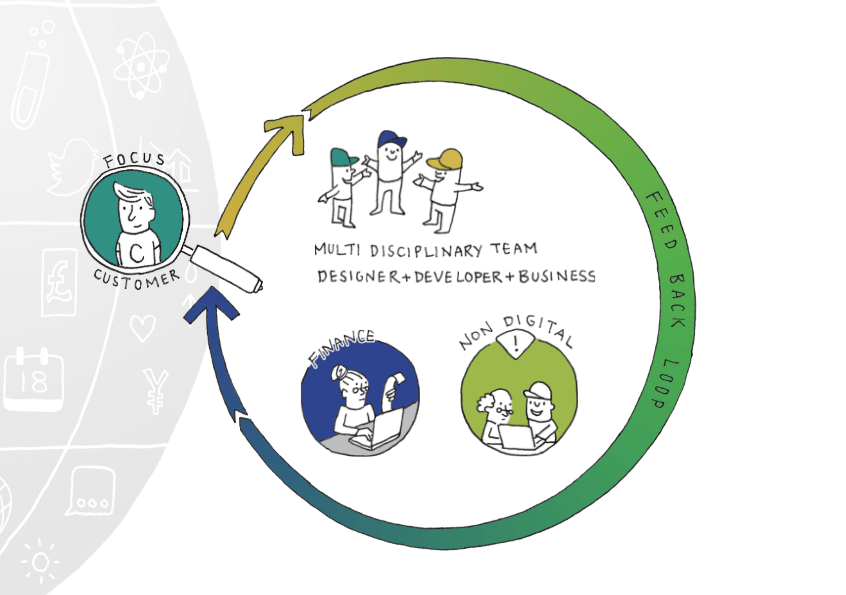

The issue is that a delivery team cannot just focus on the current context i.e. the next one or two sprints. The team has to also listen to and act on feedback from users and users need a forward view of what will be delivered when so that they can plan business change. At a minimum, key members of the team, such as the Product Owner and Tech Lead, need to be in all these conversations, ideally you want everyone to contribute.

To minimise the productivity hit of context switching, each context needs its own forum, these forums need to be prepared and run well and everyone, particularly senior stakeholders, need to understand where their input contributes rather than generating noise. See Davina’s blog on setting an analysis rhythm to see what we mean by this in a practical way.

Governance

As we are spending someone else’s money, some governance is needed but excessive bureaucracy is not. Effective decision making, particularly about spending, is critical to efficient delivery.

Talk to the sponsor about applying the GDS governance principles:

- Don’t slow down delivery

- Decisions when they’re needed, at the right level

- Do it with the right people

- Go see for yourself

- Only do it if it adds value

- Trust and verify

Make sure that your team can be trusted by them “demonstrating control”. By this I mean that are transparently demonstrating full Agile disciplines and are able to evidence that they are spending the budget wisely. If you are trustworthy you will be trusted.

Capability – Do you have people with the right skills, attitude and experience?

This an area that many Agilists find difficult because they believe, as I do, that the retrospective prime directive applies in nearly all cases; no-one sets out to do a bad job and everyone is doing the best they can in their circumstances.

However this can’t gloss over the fact that there are some people who are more productive in their role than others. It is also a fact that many good delivery people dislike “free-riders” who tend to be productivity hoovers and an organisation tolerating this will tend to lose good people to those that don’t.

A brutal hire and fire culture also kills productivity, so a balance has to be struck.

My balance on this is that if you have a weaker member of the team who acknowledges that they need to learn, they should be given the opportunity and encouragement to do so. If they don’t recognise it or aren’t prepared to learn then they need to be managed out.

For me attitude to feedback and willingness to learn is key for both contractors and permanent staff but clearly the level of tolerance of poor productivity should be lower for contractors.

In all circumstances as a leader in Agile delivery you have to be actively monitoring and managing the capability of the team. All the research into the success or failure of programmes and projects, no matter which methodology is used, highlights that the key success factor is good people.

Do the hard work at the beginning to get the right people with the right attitude. Make sure that your hiring processes is rigorous and repeatable. Get candidates to prove their skills at interview through relevant exercises e.g. you want to see developers code and user researchers electing feedback from users.